Probiotics are strain specific and must be supported by clinical studies that show benefits in target market populations.

December 31, 2019

Following the news about probiotics and the role of the gut microbiota can be confusing. One week, the microbiota seems key in finding a solution for a severe condition and probiotics can help in so many applications;1 the following week, research shows probiotics are neither effective nor safe.2 But in this age of uncertainty, there is truth to be found in the probiotics field.

The Basics

Almost 20 years ago, a World Health Organization (WHO) working committee adopted the definition of probiotics as “live microorganisms which, when consumed in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host,” and this definition is still valid today.3 Importantly, this definition recognized that evidence indicated many probiotic properties could be strain-specific. It further stated that any health benefit had to be supported based on in vitro tests and at least one clinical study, performed with said microorganism strain.

It’s All About the Strains, Not Species

Every summer, contaminated food leads to E. coli outbreaks, and people are hospitalized or even in the ICU because of it. Yet E. coli, short for Escherichia coli, is a bacterium that can be found in most healthy humans. E. coli comes in many strains; think of them like dog breeds. Some of them can live in the gut and produce vitamin K for the body, while others result in life-threatening hemorrhagic fever.4 For example, the E. coli strains K12 or STF073 are harmless, while E. coli strains H7:O157 or H4:O104 can be deadly if untreated (and, sadly, sometimes even when treated).

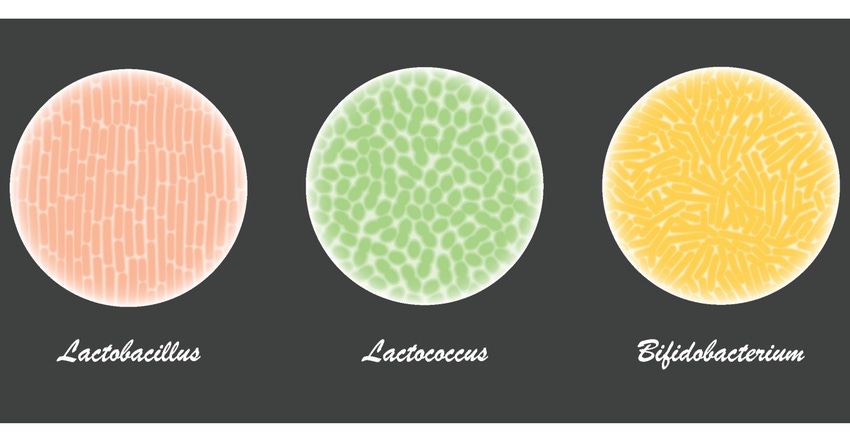

Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria are unlikely to cause harm, except in individuals with very specific health conditions such as severe immune dysfunction. However, a seminal article published 20 years ago demonstrated that strains could greatly differ in their capacity to survive passage through stomach acid or to attach to the gut mucosa within the same species.5 Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium longum are not strains, but species, and only stating the species name provides little information about the properties of the microorganism found in a product. Two probiotic products containing Lactobacillus plantarum can greatly differ in their properties: one may contain a strain that was tested for clinical efficacy and safety, while the other may contain a generic without clinical trials.

Quality, not Quantity—It’s Not About the Billions

A common misconception in the probiotics world is that more is always better. If a given Lactobacillus strain does not have the capacity to survive in the acidic medium of the stomach, attach to the gut mucosa and, when there, produce molecules of interest like immunoregulatory molecules or molecules that kill pathogens, it’s useless as a probiotic. In fact, as per the definition, it should not be called a probiotic at all. And tons of useless microorganisms, even if they’re a known Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium species, will not make it a useful one. It’s like Monopoly money: No matter how much of it you have, you can’t buy anything in the real world. In fact, it may make the product more expensive, not more efficacious.

Clinical Research: Devil in the Details

In clinical research, several technical details can tell a good study from a mediocre one, like if the number of subjects recruited was large enough to answer the research questions, whether there was a placebo group, or how rigorous the statistical procedures were. Judging these details often requires specific expertise. However, anyone can assess a couple of details: The condition(s) the probiotic improved and the makeup of the research subjects. If a probiotic strain has been clinically researched in subjects with high blood cholesterol and shown to positively impact blood cholesterol, it can be utilized as a probiotic for said function, but it cannot be claimed it is a probiotic for, say, diarrhea, until it has been clinically tested for this later condition.

Imagine a probiotic shown in clinical trials to reduce the duration of infectious diarrhea in children when given from the onset of diarrhea.6 Then, a new clinical trial in a large population shows it has no effect when given from day three on.7 At first, one could be tempted to conclude that the field is confusing, or worse, that probiotics do not work. However, just looking at the profile of the subjects in the different studies, i.e., children whose diarrhea has just started vs. children whose diarrhea has already been going on for two days—bear in mind children’s diarrhea normally last from three to five days—both studies can be reconciled. Thus, a more sensible conclusion would be that the probiotic needs some time to build up the effect, and thus should be given as early as possible when diarrhea appears.

The field of microbiota and probiotics is both fascinating and confusing. Keeping in mind a few key concepts—such as what a strain really is, the need of clinical proof of efficacy and the subjects’ profile in clinical studies—sheds light on many issues. The bottom line is these key concepts help identify the probiotic products most likely to produce a benefit for each customer’s condition.

Jordi Espadaler is chief science officer of Floradapt at Kaneka Probiotics.

References

Tsai Y et al. “Probiotics, prebiotics and amelioration of diseases.” J Biomed Sci. 2019 Jan 4;26(1):3. DOi: 10.1186/s12929-018-0493-6.

Kothari D, Patel S, Kim S. “Probiotic supplements might not be universally-effective and safe: A review.” Biomed Pharmacother. 2019 Mar;111:537-547. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.1104.

Hill et al. “The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic.” Nat Rev Gastroenterol 2014. 11:505-514

Chaudhuri R, Henderson I. “The evolution of the Escherichia coli phylogeny.” Infect Genet Evol. 2012. 12:214-26

Jacobsen et al. “Screening of Probiotic Activities of Forty-Seven Strains of Lactobacillus spp. by In Vitro Techniques and Evaluation of the Colonization Ability of Five Selected Strains in Humans.” Appl Environ Microbiol 1999. 65: 4949–4956

Szajewska et al. “Meta-analysis: Lactobacillus GG for treating acute gastroenteritis in children--updated analysis of randomized controlled trials.” Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013. 38:467-7

Schnadower et al. “Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG versus Placebo for Acute Gastroenteritis in Children.” N Engl J Med 2018. 379:2002-2014

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=800&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)