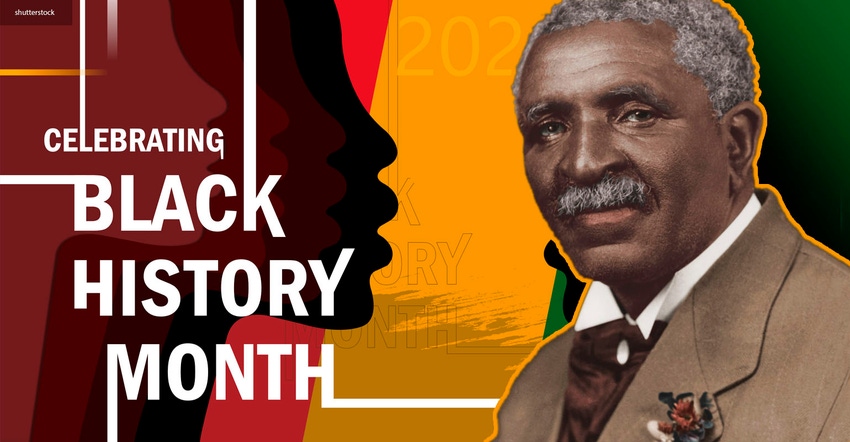

This notable botanist dedicated his life to regenerative agriculture and improving the lives of 20th century Black Southern farmers. Peanut products made his fame.

February 26, 2021

“Whenever the soil is rich, the people flourish, physically and economically. Whenever the soil is wasted, the people are wasted. A poor soil produces only a poor people.”– George Washington Carver

Farmers are the backbone of the dietary supplement and food industries, and we flourish when we care for the men and women who harvest our ingredients. This thinking was spearheaded by a man who spent half a century working to improve the conditions of crops and the American farmers who supplied them. George Washington Carver imparted practical, tangible and specific ways Black Southern farmers could efficiently and effectively increase yield and quality during the start of the 20th century. Largely remembered for his work with peanuts in the 1920s, his impact expanded much further.

As a head of Tuskegee Institute’s Agriculture Department, he urged Alabaman farmers to rotate crops and to use organic fertilizers. He preached the values of planting soil-restoring crops, such as peanuts, sweet potatoes, black-eyed peas and soybeans, to improve soil depleted by cotton crops. He issued bulletins that uneducated farmers could understand, explaining how these soil-resorting crops could be grown and what they could be used for. He devised a demonstration vehicle called the Jesup wagon that traveled dusty roads to teach small groups of famers how to improve their lives. His work with farmers formed his life’s focus on two major problems: the need for sustainability and conservation.

George Washington Carver was born into slavery during the final months of the civil war in 1864 on a Missouri farm owned by Moses Carver. George Washington Carver’s father died before he was born, and when George Washington Carver was an infant, he and his mother and sister were abducted by raiders and taken to Arkansas. An agent for Moses Carver was only able to find George Washington Carver. Moses and his wife Susan raised George Washington Carver and his brother James after the Civil War, Susan taught the boys to read and write since they couldn’t attend the local school due to segregation.

From early childhood, George Washington Carver was drawn to nature and curious about how the world worked. His deep Christian faith was developed when he was young and stayed with him his entire life, fueling his love of nature and desire to serve his community.

At 12, George Washington Carver walked 8 miles from the Carver household to Nepsho, Missouri, to attend a school for Black children. There, he lived with Andrew and Mariah Watkins. Mariah was a midwife who used medicinal herbs to help women through birth. She imparted to George Washington Carver that illness could be addressed by plants and the products extracted from them.

George Washington Carver hitched a ride to Fort Scott, Kansas, in his early teens to further his education, but he left town after he witnessed the lynching of a Black man. He was admitted to Highland College in Highland, Kansas, only to be turned away when officials learned he was Black. He landed at Simpson College, a Methodist college in Indianola, Iowa, with aspirations of being an artist. He wanted to paint the beauty of nature. Encouraged by art teacher Etta Budd, he went to the Iowa Agricultural College and Model Farm (now Iowa State University) in 1891 to study botany. He was the first African American student, and was not able to room with the other students nor was he allowed to eat with them. He eventually won over the all-white staff and students, earning a master’s degree and becoming the first African American faculty member at the college.

In 1886, George Washington Carver received a famous letter from Booker T. Washington, principal of an industrial teaching training institute for Black students in Tuskegee, Alabama. “I cannot offer you money, position or fame,” Washington wrote. “The first two you have. The last, from the place you now occupy, you will no doubt achieve. These things I now ask you to give up. I offer in their place work—hard hard work—the task of bringing a people from degradation, poverty and waste to full manhood.” George Washington Carver’s reply: “It has always been one ideal of my life to be the greatest good to the greatest number of my people possible. To this end, I have been preparing these many years, feeling as I do that this line of education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom to our people.”

George Washington Carver left Iowa and stayed at the Tuskegee Institute until his death 47 years later. When he arrived in Alabama, he had never been in the Deep South. Almost everything about Alabama’s system of agriculture appalled him, with its heavy reliance on cotton and its system of tenant farm sharecropping. Improving the practice of Southern agriculture and the conditions of poor farmers became George Washington Carver’s chief concern.

George Washington Carver came to prominence in the 1920s for his work related to peanuts, which eventually led to his creation of over 300 products from the plant. His work led to praise from Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge and Franklin Roosevelt. He had a close relationship with Henry Ford, and he helped Mahatma Gandhi develop his vegetarian diet. Thomas Edison offered him a US$100,000 salary to work in his lab in New Jersey, but George Washington Carver turned it down. In 1941, Time magazine dubbed him the “Black Leonardo.”

After George Washington Carver died on Jan. 5, 1943, his birthplace was memorialized as a national monument, the first national monument dedicated to an African American and the first to honor someone other than a president. In the years since, George Washington Carver’s likeness has been featured on postage stamps and coins—and naval vessels, parks, schools, public buildings and a bridge have been named after him.

When he died, he left his fortune to Tuskegee. However, his legacy spreads well beyond Alabama farms to include the modern-day natural products industry, which we continue to discover thrives best when committed to George Washington Carver’s vison of soil health and farmers’ welfare.

Source: “George Washington Carver: An Uncommon Life,” an Iowa PBS Documentary.

You May Also Like

.png?width=800&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)