FDA acted to reduce sodium intake in American diets by issuing a voluntary draft guidance to the food industry to reduce the salt content of food over a 10-year period, and by changing labeling requirements in nutrition facts panels.

Americans consume an average of 3,400 mg/d of sodium (1,100 mg greater than the recommended federal guidelines), according to FDA.

"When sodium intake increases, blood pressure increases, and high blood pressure is a major risk factor for heart disease and stroke—two leading causes of death in the United States," FDA noted on its site. The agency believes reducing sodium levels in the American diet will prevent hundreds of thousands of premature deaths and illnesses over the course of a decade.

To aid in reducing the average sodium consumption of Americans, in June 2016, FDA issued draft guidance for the food industry on voluntary sodium reduction, as well as updated the recommended daily value for sodium on food labeling.

Voluntary Sodium Reduction: Draft Guidance for Industry

Contrary to popular belief, adding salt to food at the dinner table is not the major contributing factor of sodium to the American diet. The guidance noted approximately 75 percent of sodium intake comes from processed and commercially prepared foods, which makes it difficult for consumers to control their consumption.

The draft guidance defines both short-term (two year) and long-term (10 year) targets to decrease the sodium content in these foods gradually. If industry meets these targets, FDA expects that average sodium consumption would be reduced to approximately 3,000 mg/d in two years, and about 2,300 mg/d in 10 years.

FDA divided the American food supply into 150 categories to establish its goals. For each food category, the agency established:

• 2010 baselines for processed and/or commercially prepared foods. These baselines represent the average sodium concentration of each food category as of 2010. FDA calculated the baselines using 2010 nutrition data to allow room to credit companies that have already reduced sodium in their products over the past seven years.

• Short-term and long-term “target mean" sodium concentrations. A target mean represents the sales-weighted average sodium concentration FDA would like industry to attain for a food category as a whole.

• Short-term and long-term “upper bound" sodium concentrations. These upper bound concentrations represent a goal for each individual product within a food category.

While developing its sodium reduction goals, FDA identified certain food categories as being significant contributors to American sodium intake. Prominent among these are pizza, sandwiches, deli meats, pasta dishes, snacks, breads and rolls. To make the most substantial impact possible on sodium consumption levels, FDA chose to calculate its baselines and target means as sales-based averages, meaning products that sell more have more influence on the average.

The agency’s webpage on frequently asked questions about sodium reduction reflects industry concern that consumers may not purchase foods with less sodium due to the different taste. According to FDA, “People usually don’t notice small reductions (about 10 to 15 percent) in sodium."

FDA’s gradual approach is an effort to adjust consumer tastes slowly over time without them noticing a substantial difference. The agency encourages companies concerned with their products’ taste to replace sodium with other flavor-enhancing ingredients, such as herbs and spices.

Sodium in Relation to FDA’s New Food Labeling Rules

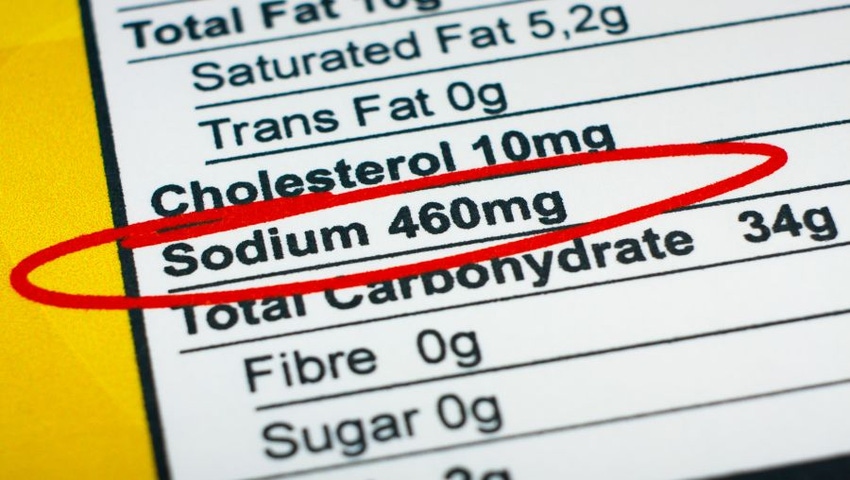

In May 2016, FDA finalized two rules mandating significant changes to food and beverage labeling. These rules go into effect for most food products on July 26, 2018. Food products manufactured by smaller companies may have until July 26, 2019 to institute the new requirements. These final rules cited the enormous discrepancy between the average consumption of 3,400 mg per day and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) panel's recommended upper level of 2,300 mg per day.

FDA also noted the substantial amounts of data that link sodium intake to numerous health conditions, such as heart disease, stroke and high blood pressure. The IOM panel's recommendation, along with other reports from authoritative bodies, provided the corroborative evidence needed for FDA to act.

Included in the rules was an updated daily reference value (DRV) for sodium. Prior to the issuance of the new rules, the DRV for sodium was 2,400 mg. Based upon the more recent nutritional and scientific data, FDA lowered this value to 2,300 mg. Thus, the percent daily value for sodium declared on any food label may increase without any formulation change on the manufacturer's part.

Comments by FDA in these final rules illustrate the agency's commitment to a multifaceted approach: "We understand that combining the nutrition facts label education efforts with other policies may be more effective in supporting healthy dietary choices … As part of supporting access to healthy foods, we continue to encourage food product reformulation, such as reducing sodium content in the food supply."

It appears the nutrition labeling changes dovetail with FDA's efforts to encourage industry to voluntarily reduce sodium content in food, in the interest of promoting healthier eating habits on the part of American consumers.

As a result of this educational outreach, foods that can claim "low sodium" or "sodium free" may become more desirable in the American marketplace. To make claims about sodium content, most products must be below certain levels per FDA reference amount for that food: "sodium free" (less than 5 mg), "very low sodium" (35 mg or less), and "low sodium" (less than 140 mg). Products with very small reference amounts (i.e., 30 g/2 tablespoons) may need to meet these levels per 50 g, as well.

While FDA’s guidance on sodium reduction is voluntary, food companies may find that reducing sodium levels in their products provide them an advantage, especially should they be early adopters. FDA's final rules on food labeling also highlight the agency's intent to update current and launch new educational programs and materials to assist Americans in understanding the new Nutrition Facts label to make well-informed and healthier food choices.

As American consumers continue to become more health-conscious and pay more attention to nutrition labels, lower sodium content may be just the thing that causes a shopper to add your product to their cart over the competition’s.

Anna Benevente ([email protected]) is a senior regulatory specialist at Registrar Corp. (registrarcorp.com), an FDA consulting firm that helps companies comply with FDA regulation. She has been assisting companies with FDA regulations since 2009, and has researched more than 370 products to determine whether they meet FDA requirements for compliance.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=800&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)