Snacking is arguably the liveliest product class in foods due to shifting definitions and innovative products with “healthy messaging."

January 25, 2017

Oversaturation has affected Western markets in the past five years. Given the amount of food Western citizens buy, it is no surprise that growth has come to a halt. In Western Europe, packaged food value sales increased by 9 percent between 2010 and 2015, while volume sales decreased by 3 percent; in North America, similar value increases were matched again by volume declines.

Yet, the world of snacks presents a breath of fresh air. Far from being tired, snacking is arguably the liveliest product class in foods at the moment. Compared to overall food sales in Western Europe, savory snacks achieved volume sales growth of 14 percent in the same time; snack bars and fruit snacks grew by 10 and 37 percent, respectively, albeit from a low base. So, how and why are snacks experiencing such a boom?

A Broad Church of Products Getting Broader

Partly, the answer lies in defining what a snack is. If one gives a limited definition and incorporates, for example, only sugar and chocolate confectionery alongside chips and cookies, then the outlook for snacks, at least in North America and Western Europe, suddenly grows darker. In Western Europe, chocolate confectionery has seen 0.5 percent volume sales compound annual growth rate (CAGR) between 2010 and 2015; cookies saw even lower growth, and sugar confectionery sales declined. Asia Pacific saw a CAGR of 6 percent in chocolate confectionery.

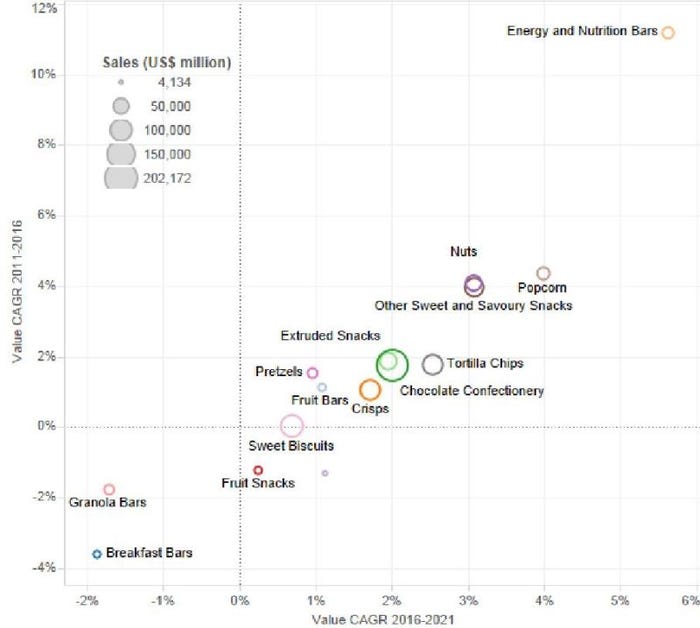

Chart

U.S. Snacking Products' Value Sales 2016 and Value CAGRs 2011-2016/2016-2021

Undoubtedly, there has been a shift to healthy snacks—or at least, snacks perceived to be healthy. Hence, while cookies struggle, Mondelez's Belvita brand has grown by 183 percent in a five-year period, equivalent to US$166 million in additional sales. That is just in Western Europe—globally, the brand has become a priority for the company, achieving nearly $700 million in sales in 2015. Growth remains rapid, in part, because it has successfully communicated that it is a "healthy" brand.

“Healthy" is an amorphous term; is a Belvita cookie “healthy" because it is not chocolate, or does a product have to have legitimate, certified health benefits to be considered healthy? This looseness of terminology is something manufacturers have been able to capitalize on, with Kellogg and Mondelez, for example, promoting their products as generally healthy without possessing specific claims; Nakd, acquired this year by Belgian cookie manufacturer Lotus Bakeries for EUR70 million, promotes itself as gluten-, wheat- and dairy-free, appealing to the recent popularity of free-from products.

More recently, products from companies such as Clif Bar & Co. have become more visible across the West, particularly in the United States, the U.K. and Germany. These brands promote themselves as high-protein energy bars, and target gym-goers and mountain hikers. Clif packaging, for example, displays a man hiking, with the tagline “feed your adventure." The brand more than doubled its market share and sales in five years, and was on course to account for 7 percent of global snack bar sales by the end of 2016.

The Future of Snacking

The scope of what can be considered a snack is shifting, with many dairy products moving into a snacking position. Danish dairy producer Arla is one leading example, having launched Scandinavian delicacies quark and skyr in Finland and, since then, elsewhere in Europe, in single-serve snack pots. Like Clif, these products forcefully communicate their high protein content on the packaging. Since launching in Germany and the U.K., Arla has achieved 2 percent in both countries' fromage frais and quark segment. Alongside the United States, these two countries tend to dominate new snacking trends, and both have a high spend on traditional snacks. Euromonitor International research indicated markets with a high spend on conventional snacks are more willing to branch out and try new products.

Of course, the idea of traditional snacks is heavily geared toward Western snacking habits. In Asia Pacific, for example, traditional snacks tend to be pastries, cakes and cookies. There is certainly room for expansion for chocolate and sugar confectionery in these markets. But it will be tough to achieve this growth outside wealthier classes who are able to afford, for example, chocolate, which is roughly 2 to 3 times more expensive than cookies, pastries and cakes.

Globally, there will be room for “traditional" snacks. The average German consumes 160 50 g bars of chocolate per year at a rate of three a week. While they will eat less by 2020 (per capita consumption will decline by 200 g over the next four years), it is important to emphasize that these still have a significant role to play. In truth, however, the movement toward more snacking occasions will result in a more diversified array of snacks available. Snacks will continue to be one of the most innovative segments of packaged food for years to come.

Jack Skelly is a food analyst at Euromonitor International.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=800&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)